An extended model of this essay first appeared in Artwork and Illustration for Science Communication © 2022 Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Artwork and science could be humankind’s two most noble enterprises, and so they have lived culturally hand-in-hand ever since our first purposes of paint to depict animals, folks, and motion on the partitions of caves. The good mathematician-philosopher Jacob Bronowski argued that they share frequent origins inside the human psyche, pushed by two parallel and highly effective internal forces: our persistent curiosity and our vivid creativeness.

The image and the metaphor are as essential to science as to poetry.

In Bronowski’s phrases, “The image and the metaphor are as essential to science as to poetry” and, “the discoveries of science, the artworks, are explorations…of hidden likeness. The discoverer, or the artist, presents in them two points of nature and fuses them into one. That is the act of creation, during which an unique thought is born, and it’s the similar act in unique science and unique artwork.”

As scientists, we arrange and codify our explorations, constructing upon the organized curiosities of our forebears. As artists, we craft our “information of the senses” into expressions of curiosities and perceptions, deciphering and evoking human feelings. Each of those endeavors contain experimentation and imaginative and prescient, in addition to errors and failures. Science advances by pushing the boundaries of commentary, proof, and logic whereas staying conscious that concepts are weak. Artwork advances alongside remarkably parallel tracks, relentlessly probing boundary zones between commentary, interpretation, and creativeness, generally attaining brilliance, and different instances falling flat.

In 1505–06, for instance, Leonardo da Vinci wrote Codex on the Flight of Birds, having studied how birds fly and imagining how people would possibly mimic them. His concepts about human flight had been abject failures, however his copious illustrations turned timeless masterpieces of imaginative engineering.

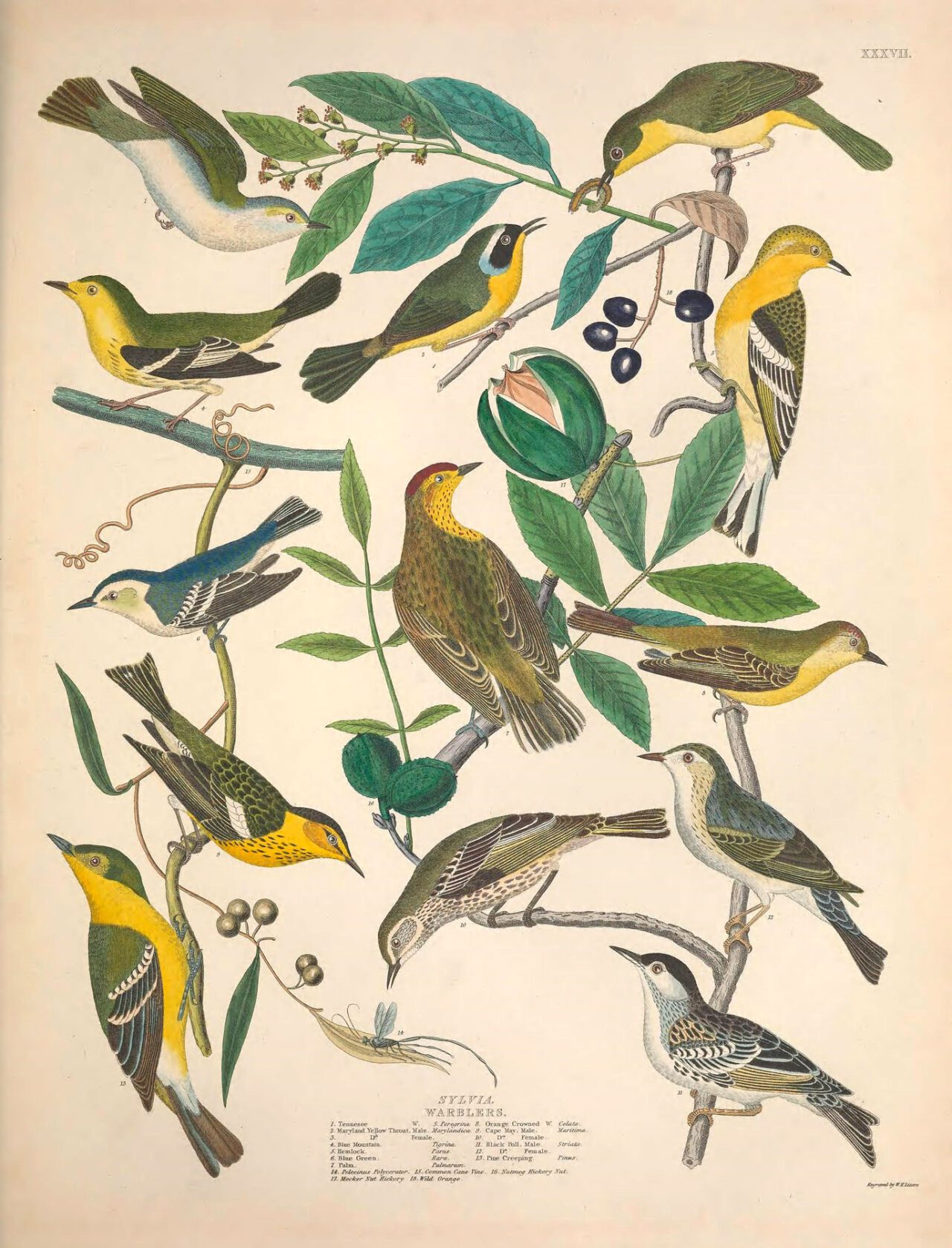

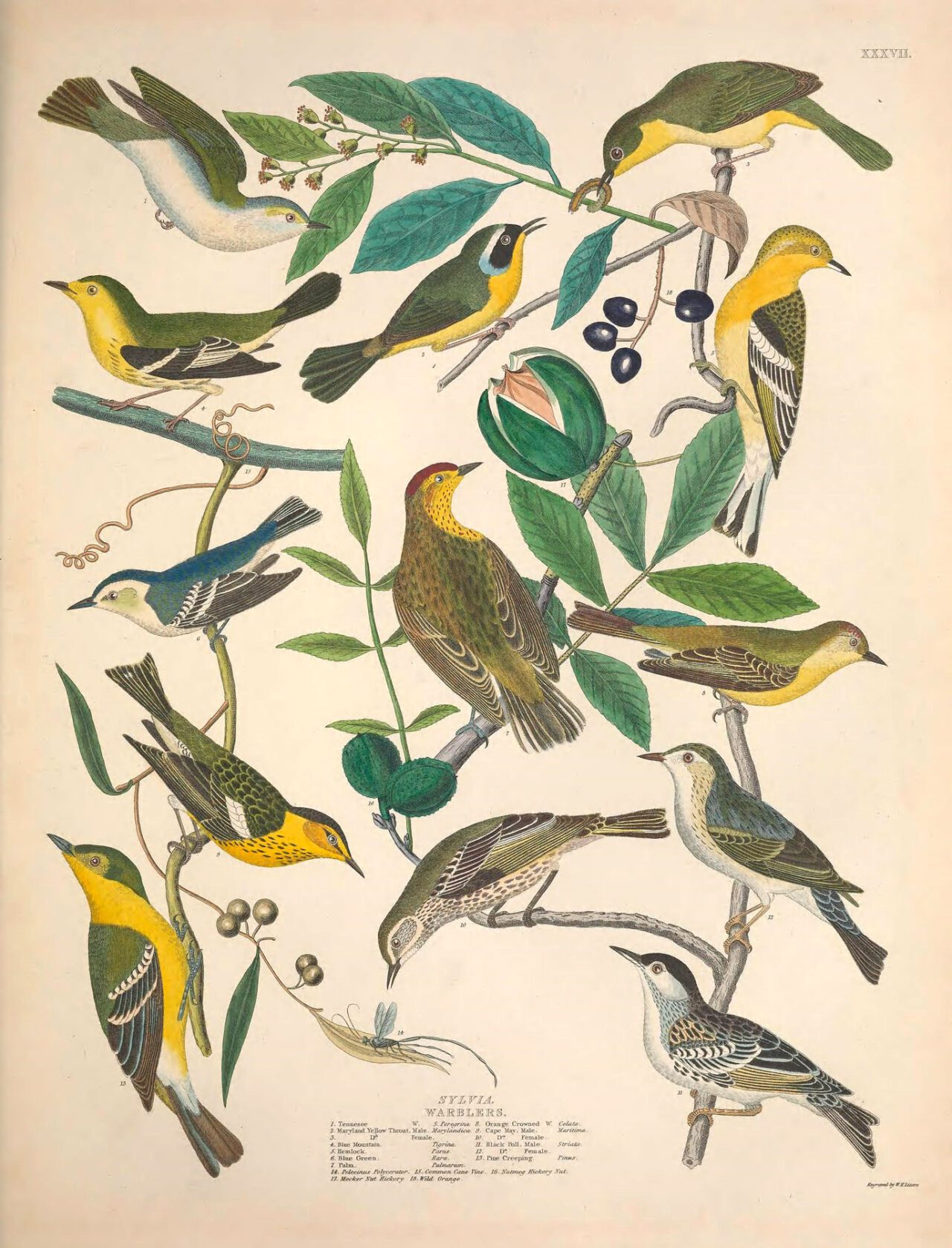

By the 18th and nineteenth centuries, ornithologist-explorers corresponding to Mark Catesby, William Bartram, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon had been making elementary scientific contributions whereas additionally exploring beforehand uncharted creative areas. For instance, it was the British Museum’s ornithologist John Gould—well-known for ground-breaking lithographs largely created by his spouse, Elizabeth—who first acknowledged a number of distinct species amongst finches and mockingbirds collected by Charles Darwin on the Galápagos Islands, serving to pave the way in which for Darwin’s foundational insights into evolution by pure choice.

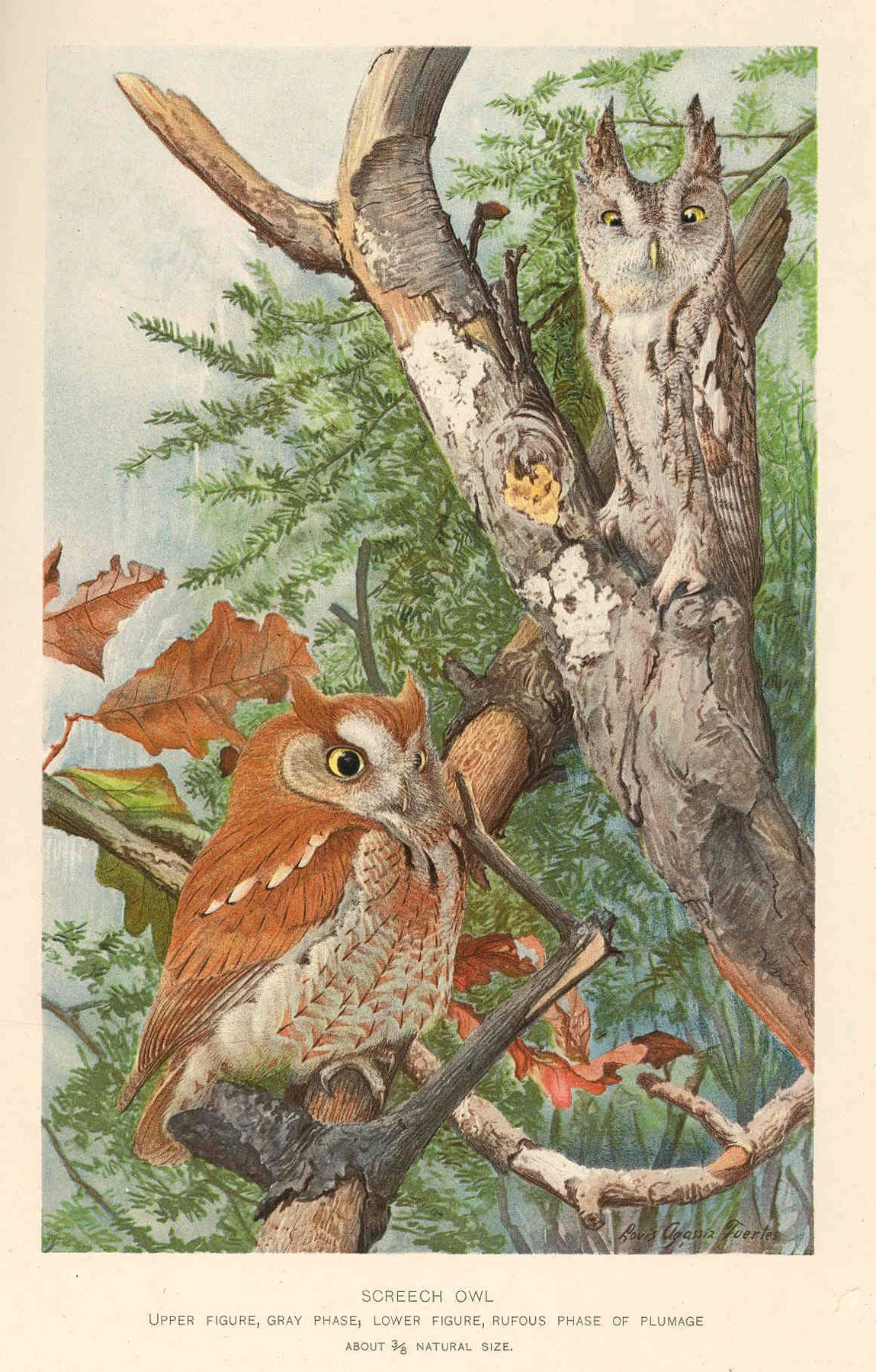

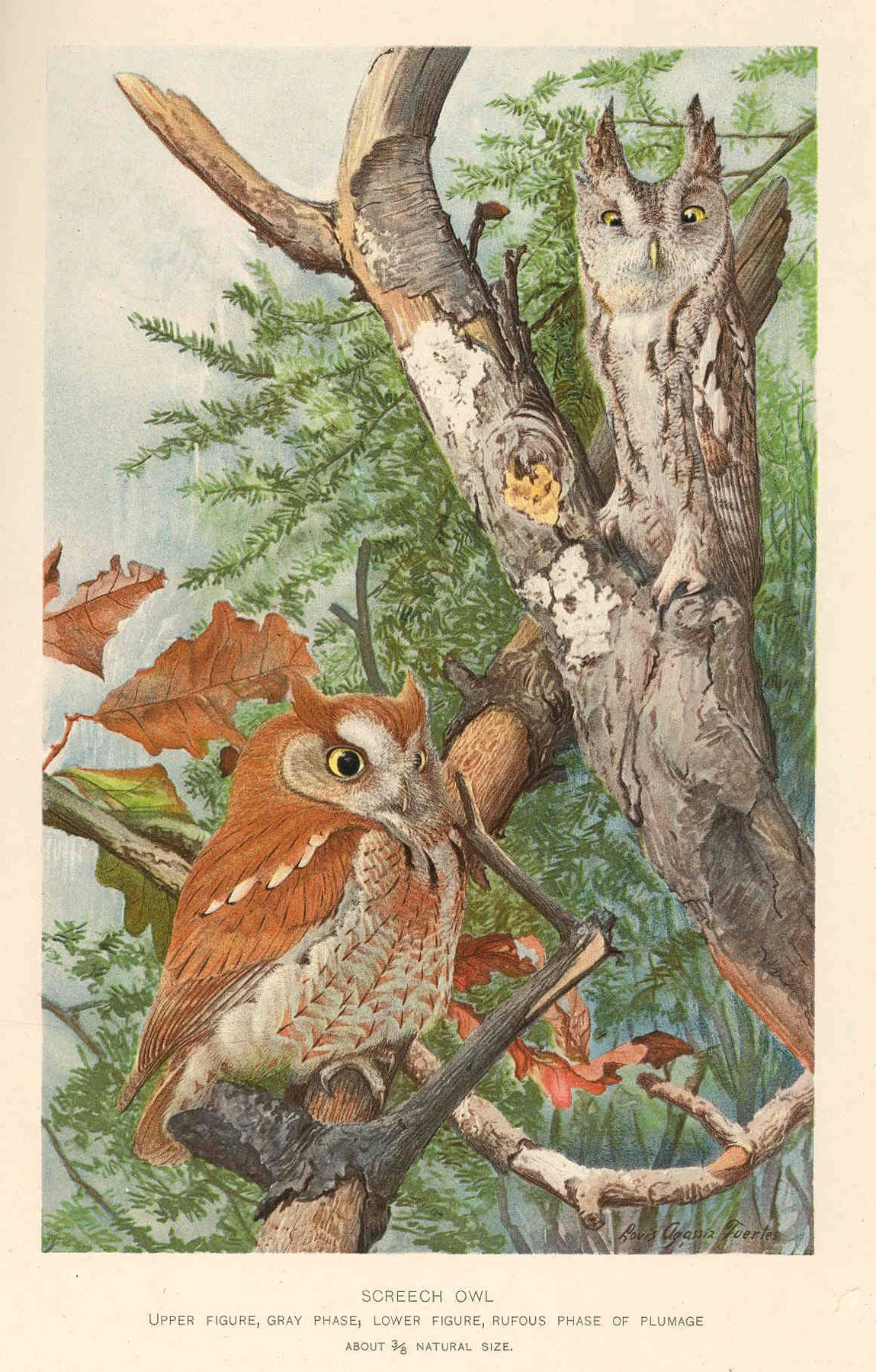

To today the world’s nice pure historical past museums routinely carry artists and scientists collectively with a purpose to catalog and perceive the pure world, and to encourage the general public about its wonders. Pioneering naturalist painters of the early twentieth century like Liljefors, Fuertes, Rungius, Jaques, Sutton, and Peterson graced each the partitions of museums and the pages of influential books, successfully blurring the distinctions between science and artwork in our self-discipline.

Common Accessibility and Hanging Selection

The interweaving of artwork with science on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology owes its origins to a Cornell professor within the early twentieth century. Arthur A. Allen, the founder and first director of the Cornell Lab, understood that birds possess two nice powers: common accessibility and putting selection, making them excellent topics for scientific breakthroughs about type, operate, and ecological relationships. Equally, nevertheless, Allen appreciated how deeply birds attraction to the human creativeness, thus making them focal topics in portray, sculpture, poetry, music, and folklore by means of all ages and cultures.

As luck would have it, the junction of nineteenth and twentieth centuries produced a gifted younger chook artist named Louis Agassiz Fuertes, who’s sometimes called “Audubon’s successor.” Fuertes lived in Ithaca, attended Cornell College, and have become quick pals with Arthur Allen. This influential friendship helped reinforce Allen’s recognition of how powerfully birds stimulate the human psyche—each as topics of science and as inspirations for artwork.

It’s tempting to take a position that Allen, together with his naturalist’s instinct, acknowledged that birds activate either side of our mind. This concept gained foreign money a lot later as a preferred idea in neurobiology—that the left-brain manages vital options of mind, speech, logic, and reasoning; whereas the right-brain handles much less linear features—the creative, emotional, and religious parts of our persona.

Birds commingle our mind with our aesthetics. They seize each our minds and our hearts.

Birds possess the extraordinary energy to mild up either side, usually concurrently. We examine them, rely them, be taught nature’s secrets and techniques from them, whilst we marvel at them, write songs and poetry about them, love them, and even worship them. Maybe greater than another group of organisms, birds commingle our mind with our aesthetics. They seize each our minds and our hearts.

As his lengthy profession at Cornell progressed, Arthur Allen more and more centered on pioneering nature images, pure historical past filming, sound recording, and studio productions for most people. Amongst his dozens of scholars had been proficient artists corresponding to Robert Mengel and George Miksch Sutton who integrated sketches, technical illustrations, and coloration work into their publications. Allen’s launch of an annual journal referred to as The Dwelling Chicken in 1960 was a milestone in ornithology, largely as a result of every subject interspersed dozens of line drawings, scratchboards, work, and even poetic verse amongst its dozens of technical papers.

Dwelling Chicken in its unique type was a scientific and creative success, but it surely circulated to only some hundred scientists, supporters, and libraries. By 1981, when Charles Walcott arrived on the Lab to grow to be its new director, birdwatching was gaining momentum as a preferred out of doors pastime. Walcott made the daring transfer to transform Dwelling Chicken into the award-winning coloration quarterly journal that it stays to today. Because the Lab’s signature journal, Dwelling Chicken continues to pair extraordinary images and illustration with top-flight science journalism written to stimulate, educate, and encourage a broad public viewers concerning the wonders of birds and their locations, habitats, behaviors, and vulnerabilities. On this manner, each subject strives to be a quintessential melding of artwork and science.

artwork Finds a House on the cornell Lab

Right now the halls, partitions, and grounds of the newly renovated Johnson Heart for Birds and Biodiversity are adorned with work, prints, and sculptures by high-quality artists various from the normal realism of Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Frances Lee Jaques to the poignant sculptures of Todd McGrain and the witty, colourful avian graphics of Charley Harper. Two colossal murals grace our Guests Heart. James Prosek’s Wall of Silhouettes, impressed by Roger Tory Peterson’s iconic endpapers from A Discipline Information to the Birds, pays homage to the position of birdwatching within the scientific examine of birds and their habitats. Jane Kim’s From So Easy a Starting is a monumental 2,500 square-foot mural presenting a surprising journey by means of 375 million years of evolution, starting with the earliest marine tetrapods and ending with a vibrant celebration of recent birds and their international prevalence.

Maya Lin’s elegant Sound Ring is an interactive audio-sculptural part of her What’s Lacking? memorial to threatened and extinct biodiversity all over the world. Todd McGrain’s evocative two meter tall Passenger Pigeon longingly faces skyward simply outdoors the Lab’s entrance, considered one of 5 items in his dramatic Misplaced Chicken Mission. Hidden alongside a forested path amidst Sapsucker Woods is a fascinating, egg-shaped stone obelisk donated and constructed in situ by the artist Andy Goldsworthy. Nearer to the constructing, a life sized, gleaming stainless-steel Whooping Crane entitled “Invitation to the Dance,” by Kent Ullberg, was unveiled in 2018 to honor Dr. George Archibald for his analysis on cranes as a Cornell graduate scholar, and his subsequent founding of the Worldwide Crane Basis.

the bartels science illustration program

Wonderful artwork of the very best caliber percolates by means of the Lab’s science and outreach, in no small half due to the imaginative and prescient of Phil and Susan Bartels. In 2003 they helped the Lab set up the Bartels Science Illustrators residency program. This distinctive and extremely aggressive annual fellowship has allowed the Lab to host a outstanding sequence of early-career artists who be part of us at our headquarters in Ithaca, often for a 12 months. Artists come from all corners of our nation and past, difficult themselves and the numerous scientists round them to discover either side of our brains.

Their kinds and favored media are as different as artwork itself, and over time their contributions to the Lab’s scientific and public outputs have been prodigious. Whereas studying from Lab consultants and our scientific collections precisely how birds are formed and feathered, Bartels Illustrators have given again to the Lab and the larger science communities by creating native area guides, participatory science supplies, information visualizations, technical illustrations, playful cartoons, and even cowl artwork for magazines and journals.

Many people fell in love with birds as a result of they stimulated our creativeness and captured our hearts in addition to our minds. As every Bartels Illustrator arrives on the Lab, their work jogs my memory that ornithology is a very visible science. Their work jogs my memory of Bronowski’s profound perception that creativity and evolutionary progress in each science and artwork stem from the identical, remarkably human union of curiosity and creativeness. The very existence of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology is a celebration of this union.

Concerning the Writer

John W. Fitzpatrick served because the Government Director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology from 1995–2021. Learn extra about Fitz, together with each his scientific profession and his paintings, on this profile from Dwelling Chicken journal.

Concerning the Bartels Science Illustration Program

The Bartels Science Illustration residency helps illustrators who’re simply beginning their careers to construct their portfolios by engaged on tasks on the Cornell Lab. Their work is revealed frequently in Dwelling Chicken journal, our All About Birds web site, participatory science supplies, and in scientific publications.

View the work of the 30+ proficient illustrators which have been a part of this system because it started in 2003. For extra data go to the Bartels Science Illustration Program web site or contact program coordinator Jillian Ditner.