“Once we had been little and the police would raid our homes in the midst of the evening, we’d see individuals leaping over partitions and operating away. My grandmother would get up all the youngsters in the home, collect us collectively, and inform us to learn out loud, so the police would know that school-going, common kids lived there. I at all times discovered this so unusual. Why had been we continually instructed to cover, to run? What crime had we dedicated that made us really feel that our existence was dishonest?” shares Naseema Khatoon.

Naseema, 39, was born and raised in a red-light space, experiencing firsthand the stigma and neglect confronted by intercourse employees and their kids. In the present day, having damaged free from the cycle of poverty, she has turn out to be a robust voice for the marginalised.

“It’s after I was enrolled at school that I developed a way of inquisitiveness about my identification. I might be, for the primary time, in an setting the place individuals would ask me my full title and the place I used to be from. However I used to be instructed to not inform individuals the place I lived,” Naseema tells The Higher India.

Life in a red-light district

Naseema’s house was Chaturbhuj Sthan, a red-light district in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. Named after a Vishnu temple, the realm has traditionally been house to intercourse employees and tawaifs; its spiritual title doesn’t protect the group from societal stigma.

“Why ought to I not inform individuals who I’m and the place I come from?” Naseema remembers asking her father, who shortly shut her down.

“The ladies from faculty would all stroll house collectively, however they’d take a protracted wounded path to keep away from my gully. They had been instructed to, so I’d go alone,” she says.

As a baby, Naseema was a witness to frequent police raids in her neighbourhood. These experiences left an enduring impression, and it was throughout this time that she started to completely perceive the marginalisation her group confronted.

The fixed worry of the police, the compelled hiding, and the necessity to continually run weren’t simply exterior pressures; they profoundly formed her self-perception and her battle to outline her identification.

“It’s laborious to outline your self as a daughter of a red-light space and never a intercourse employee. This can be a idea that’s remarkable to the surface world,” she says. However Naseema by no means let go of her need to outline herself past what the world compelled on her.

“Simply as somebody who has a small vegetable stall that he pushes round on the street, wouldn’t need their youngster to proceed doing the identical work they do, a intercourse employee additionally doesn’t need their youngster to proceed to do the identical. She desires higher for her youngsters,” Naseema displays.

‘I used to be at all times so scared’

In 1995, when Naseema was a younger teen, IAS Rajbala Verma, who was posted as a district Justice of the Peace, began some programmes to assist intercourse employees within the space be taught abilities, corresponding to embroidery, and get entry to healthcare. Naseema took half in a single such programme — ‘Higher Life Choice’. She had already learnt embroidery from her mom, was expert at it, and stood out. However even then, she struggled with the anxiousness of getting to reply sure questions.

“I used to be at all times so scared that I wouldn’t even converse. As a result of what if that dialog results in them asking me the place I’m from?” she admits.

At simply 13 years outdated, she was compelled to depart faculty and transfer to Sitamarhi to reside along with her maternal grandmother. Nonetheless, by this time, she had already resolved to construct a life for herself, one which would want no hiding.

“I had heard about an organisation there that was serving to adolescent ladies. I didn’t know what they did or how they might assist. I used to be certain that if I simply tried a little bit, I might determine my life out and make one thing of myself. So, I locked myself in a room for days, refused to eat or converse to anyone, till I used to be taken to the place that organisation was,” she says.

“My father stored asking why I needed to go there, and I might say that there’s a pal that I actually need to meet,” she chuckles. Her persistence paid off, and someday she met with the individuals from ‘Adithi’, an organisation that works for underprivileged girls.

The very subsequent day, Adithi employees got here to her home and urged her father to let her turn out to be part of the organisation the place she would be taught invaluable abilities and switch her life round. “I used to be so shocked after they got here to our home. It was like my legs had turn out to be jelly and the cola that I used to be presupposed to serve them, wound up on their garments. I chortle as I say that now, however that day I might have died of reduction,” she says.

She labored with the organisation until 2002, turning into a talented micro-level planner and coach. Her years in Sitamarhi with Adithi taught her concerning the legislation, youngster rights, and the security the Structure grants each citizen of this nation.

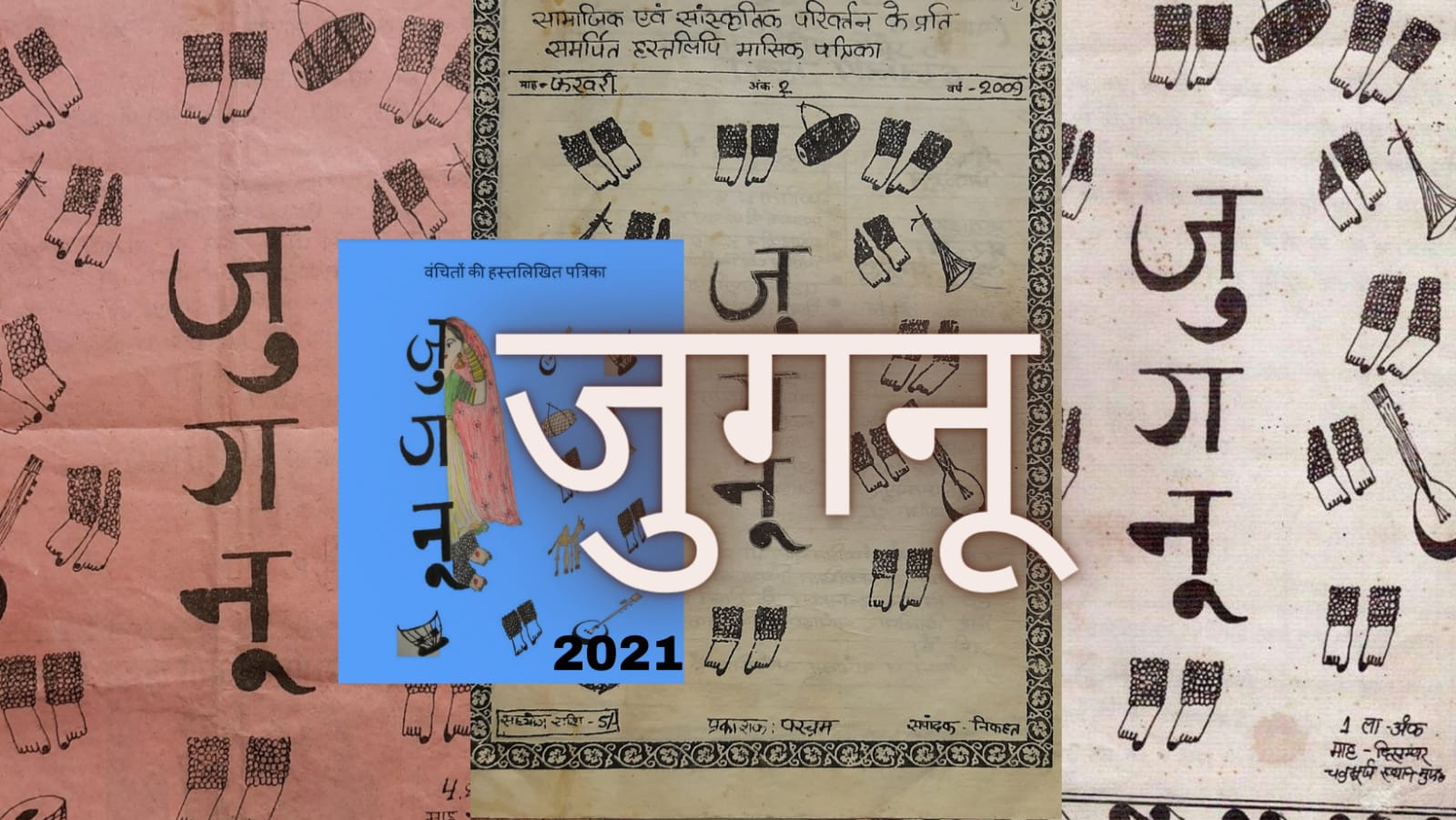

‘Jugnu’: The place kids categorical their goals

When Naseema got here again to Muzaffarpur in 2002, she noticed the problems plaguing her house city with a renewed sense of understanding.

“There was a raid within the space proper subsequent to us, girls had been arrested and brought away with out the presence of a feminine constable as a result of these guidelines, for some motive, don’t apply right here,” she says.

“The subsequent day, I sat at my father’s tea stall, watching because the police rounded up individuals from the realm. A gathering was going down, led by the ‘Samaj Sudhar Committee’, the place they instructed the ladies they might be taught abilities like tailoring, embroidery, and different jobs supplied by authorities schemes. When the ladies requested after they might begin working and the way quickly they’d get the cash, they had been instructed it might take six months to arrange,” she shares.

“When requested how they might earn a residing within the meantime, the committee took it as an insult. As if we aren’t allowed to ask questions that dictate whether or not we get to eat two meals a day or not,” she provides.

Naseema was conscious of the challenges confronted by the youngsters locally. When the girl, usually the first breadwinner, is arrested, who takes care of the household? The dependents, particularly the youngsters, are left to endure. “And if there’s a younger lady within the family, what choices does she have?” she asks.

Naseema’s work with Adithi, alongside along with her growing involvement in group points, led her to begin a community-based organisation known as ‘Parcham’, that means ‘flag’ in Hindi. Parcham was not an NGO; it was a grassroots organisation constructed by the individuals of the group, for the individuals of the group.

“I regarded round and noticed what the state of affairs was by way of training, youngster rights, employment, and was attempting to have a look at alternate options, of which there have been none,” she shares.

“Even after I interacted with the media to talk about these points, they’d in some way not point out that these are the youngsters of intercourse employees, not intercourse employees themselves, simply to sensationalise the studies,” she shares.

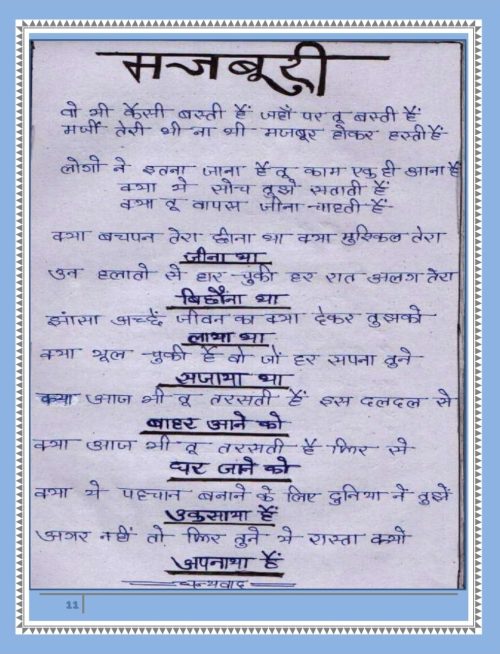

Whereas working with Adithi, Naseema had helped begin {a magazine} named Injoriya, that means ‘an evening full of sunshine’, impressed by the grownup training ‘prod’ programmes run by the Authorities within the Seventies. These programmes helped older girls be taught to learn and write, and the fabric they created was collected and was {a magazine}.

“I assumed, why not convey the identical concept to my group? {A magazine} made by the individuals of the group, telling our personal tales,” she says.

“We determined that if nobody else would write the reality about us, we might. Although many in our group couldn’t learn or write, we thought it didn’t matter if our writing wasn’t excellent — we might nonetheless write and share our voices,” she provides.

In 2004, she began Jugnu (that means ‘firefly’), a publication designed to amplify the voices of the marginalised. The primary version, a modest four-page photocopied situation, was printed with the assistance of native funds. In the present day, it’s a 36-page-long journal, with 10 lively reporters from Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Mumbai and Bihar.

“We now have a rule right here in Jugnu, everyone who’s related to us carries round a replica with them. If any person asks them who they’re, and the place they arrive from, they will simply say that they’re a Jugnu reporter,” Naseema proudly shares.

Jugnu quickly grew to become greater than only a journal; it grew to become a platform for youngsters to specific their goals, hopes, and struggles. One of many key columns within the first version was, “What’s our dream?”; a query hardly ever requested of youngsters from such communities. “We requested that query, and the youngsters would come and write what they needed to turn out to be,” she shares.

Turning into a voice for marginalised communities

M D Arif, a 24-year-old who used to attract and paint for Jugnu when he was seven, wrote that he needed to turn out to be a police officer. “Within the first few editions, I might usually draw. As soon as, I wrote for the ‘What’s our dream’ column. However now, I write about extra advanced issues that we see round right here in Muzaffarpur,” he shares, including, “That features youngster labour and identification politics.”

One particularly poignant piece he labored on covers the lives of intercourse employees who’ve given up their occupation because of outdated age. “I spoke to individuals and located that regardless that it has been years since they’ve retired, they nonetheless name themselves intercourse employees. It’s so deeply ingrained in an individual’s identification and there’s actually nothing incorrect in that both,” he says.

An lively member of Parcham and now a member of his school’s NSS staff, he usually conducts conferences, telling individuals about their rights and instructing them ask for them. “Jugnu gave lots of us the liberty to talk about ourselves, who we’re, and the place we come from; with out hesitation, with out worry,” he smiles.

As a lot as Naseema needed to proceed her work, by 2012, the journal had gone dormant as she moved to Rajasthan and began a household. However the dream by no means died. In 2021, she revived Jugnu with a renewed give attention to increasing the journal’s attain past Muzaffarpur. Now Jugnu was not only a journal of the red-light district — it represented marginalised communities throughout Mumbai, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

“Not lots of people know me in Rajasthan, however individuals do know Prem,” says Naseema, wanting again on the outstanding journey of Premnath, a 20-year-old from the Kalbeliya group in Barmer, Rajasthan.

Prem met Naseema in 2018 at an occasion and shortly grew to become concerned with Jugnu, writing concerning the nomadic tribes of Rajasthan. Rising up, as he noticed his mother and father having to beg to convey meals to the desk, he knew that he wouldn’t be capable of proceed his training for much longer.

“Our individuals had been nomads. We by no means settled and because of that, we don’t have any land to name our personal. With out an deal with and IDs, we can’t get correct documentation. If somebody from our group passes on, there are possibilities that we’d must attempt just a few villages to verify if any person would home our useless,” he says. And these are the issues he writes about in Jugnu, in the present day.

“I’ve managed to get a school training due to Jugnu,” he shares. A final-year political science main, he has turn out to be an lively author and reporter, shedding gentle on the problems his individuals face.

Empowering kids via ‘Police Paathshaala’

Naseema fondly remembers the time she inspired Prem to go to the collector’s workplace and current him with a replica of the journal. Although hesitant at first, Prem took the initiative and impressed the collector along with his willpower. When Prem talked about the challenges of finding out on the Gaushala (cow-shed) because of lack of electrical energy at house, the collector instantly took steps to rectify the state of affairs.

“That is the place we realised how this journal may help us,” says Naseema. “It’s not nearly me. It’s about any marginalised group that feels unheard.” Reporters deal with the journal as their very own structure, and Naseema encourages them to share it with others. “If individuals pay you the help funds, nice. If not, it’s by no means a waste. It can at the very least make them realise that you’re a reporter or author, somebody highly effective.”

In November 2023, Naseema additionally began a pioneering initiative, known as Police Paathshaala, in her hometown. The programme goals to vary the best way kids of Chaturbhuj Sthan interact with the police. Officers educate the youngsters, play with them, and even convey them desserts.

Naseema displays on the stark distinction between her childhood and what these kids expertise in the present day. “After I was little, I used to be at all times instructed to cover from the police, to worry them. However these youngsters? You need to see them bounce round and boss the officers, it’s fairly humorous!”

The programme started in a spare police room that was going to waste and has since grown from 15 kids to over 100. Many of those kids, like Naseema as soon as was, are faculty dropouts who face societal stigma. But, they proudly establish themselves as “the youngsters of Police Paathshaala”. Arif, along with his goals of being a police officer nonetheless intact, carefully works with these officers.

Regardless of regulatory hurdles, the objective stays to make the journal worthwhile, so the youngsters concerned can profit from the funds raised. For now, reporters obtain copies of the journal and hold no matter help funds they will accumulate from distributing them. Monetary help from donors, such because the MG Charitable Belief within the US, has been essential in printing the journal, with the primary 100 copies printed in 2021 because of their help.

“If you wish to see change, work for these youngsters — they’re the longer term,” Naseema says. “When Prem turns into any person, and he’ll, he’ll carry this goodness ahead.”

Edited by Arunava Banerjee; Photos courtesy Naseema Khatoon